Last week we were treated to an unusual find during one of our dives off of Maui. There on the sand was a strange, black, partially-circular object composed of radially symmetrical segments. Was it plastic? Metal? With that symmetry, surely it was man-made.

But no, we’d seen something like this a few years before – it was part of a whale barnacle! Ten feet away from it we found its other half.

Every winter we keep our eye out for these lucky finds. Sometimes we find them soon after they have fallen off. If that is the case, the underside of the barnacle is covered with black whale skin (this one even had the flesh of a different species of barnacle, a gooseneck barnacle, still attached to it). If we find one months after it has fallen off, it has been picked clean by marine organisms.

Left: Whale barnacle found (in two pieces) soon after falling off a whale, showing black skin embedded in barnacle (60 mm). Right: Barnacle found months after falling off of whale, picked clean by marine organisms. Photo: P. Fiene.

Until this year, all the barnacles we’d found had been intact. This one was unusual in that it was broken into two pieces. We don’t know exactly why. But, it allowed us to see – and not just read about and imagine – one reason the barnacle’s white shell stays so firmly attached to whales during the thousands of miles of migration, during their spectacular breaching, and through all sorts of sometimes violent male-on-male aggression. More on that later.

A humpback whale can have up to a thousand pounds of these barnacles attached to it! This may sound like a lot, but when compared to how much a whale weighs (35-40 tons), hundreds of pounds of barnacles on a whale is comparable in weight to, say, an aloha shirt and slippers on a human. And these are not just your garden variety barnacle. They are Coronula diadema, a species of acorn barnacle that lives only on whales, primarily humpback whales.*

Barnacles live on many parts of a humpback whale, from the throat area to the pectoral fins to the tail as seen in this photo taken off of Maui by Andy Schwanke.

Barnacle species that have evolved to live on whales are treated to a constant flow of water from which they can strain food particles. The barnacles position themselves in the places on the whale that experience the best water flow characteristics. It is believed that the barnacles are generally not harmful to the whale and might possibly even be beneficial in some cases as a defense or in competition between males.

Just how do these barnacles get on the whale to begin with? Adult whale barnacles are hermaphrodites. They fertilize the eggs of adjacent barnacles with a (proportionately) very long penis. The fertilized eggs develop into larvae which are then released into the water in the Hawaii wintering grounds. After further development as free-swimming larvae in the ocean, they are able to detect chemicals given off from a whale’s skin.** These chemicals cue the tiny larvae to settle on and attach to a whale’s skin, metamorphose into juveniles, grow, and secrete an incredibly sticky cement that tightly bonds them to the whale. Next, they begin to produce six vertical calcarious plates which will fuse to become the formidable circular shell within which the animal will live.

This shell is not solid material though. Cavities are built into the shell all around its circumference. These spike-shaped cavities “pull“ the whale’s skin into them as the shell grows.*** The whale and the barnacle shell are then almost locked together. Because this barnacle was broken in two we were able (with the help of a Dremel tool) to actually see these cavities for the first time. And, as expected, they were filled with black whale skin! Skin also grows up around the base of the shell, leaving it firmly embedded and making it reportedly very difficult to dislodge.

Arrows show where black whale skin has been “pulled” up into cavities in the barnacle’s shell. Photo: P. Fiene.

Given that the barnacle animal itself is cemented to the whale and given the interlocking-shell-and-skin configuration, it is a wonder that they ever come off. But they do!

Well-known researchers Mark Ferrari and Debbie Glockner-Ferrari have studied humpback whales in Hawaii for 39 years. They have first-hand knowledge of whales losing barnacles while in their Hawaii breeding grounds. Mark recalls that in 1987 they saw a yearling on separate occasions approximately a month apart. Because this individual was lethargic they were able to approach closely enough to actually see the barnacles and document their disappearance. He estimated that about 50% of the barnacles were lost during this time. And the reason they could tell that barnacles were being lost is because when a barnacle falls off, a perfectly circular scar is left, as you can see in this photo they provided below.

Whale head showing adult barnacles and circular scars where barnacles have fallen off. Also showing many juvenile barnacles growing around the eye and all over the body. Maui, Hawaii. Photo ©Mark Ferrari, Center for Whale Studies, under Federal Permit #538.

Some of the reasons barnacles fall off have to do with male whales using their barnacle-encrusted pectoral fins as weapons in competitions with other male whales. They might also be knocked off when whales slash at tiger sharks or false killer whales in defense, something Mark and Debbie have witnessed themselves.

But most seem to fall off after about a year as part of a natural cycle. A French researcher reported that humpbacks taken by whalers soon after they had arrived in Madagascar for the winter season had large barnacles attached, but by late winter the whales that were being caught and killed had no barnacles. Instead the whales had barnacle larvae beginning to attach. By spring, the whales had small adult barnacles.* Photos taken in Hawaii seem to corroborate this approximate year-long life cycle. Scars show adult barnacle loss, while tiny new barnacles can be seen beginning to grow, as in the photos below and above.

Whether they are genetically programmed to die after about a year or whether some environmental factor in their breeding grounds causes them to die is, to my knowledge, not known. Could it be that Hawaii’s semi-tropical waters don’t supply the right (or enough) food, are too warm, harbor diseases (predators, parasites?) or have insufficient available oxygen for the adult barnacles? Could UV radiation be too intense? Could the whale slough more skin or experience an altered immune response (in turn affecting the viability of the adult barnacles)? Perhaps some of these factors have been examined already but I could not find such studies in my search.

Adult barnacles and juvenile barnacles growing on a whale fluke. Maui, Hawaii. (Long, fleshy gooseneck barnacles can be seen growing on the sides of the white whale barnacles. Photo ©Mark Ferrari, Center for Whale Studies, under Federal Permit #393-1772-01.

Considering the millions of pounds of barnacles that travel to Hawaii on the bodies of humpback whales, and that many barnacles are falling off here, it seems surprising that to find one while diving is so rare. But when a barnacle falls off, the odds of it occurring in water visited by divers is small. Divers dive in such a tiny fraction of ocean waters, and usually in water shallower than most whales frequent. When you add the small size of the barnacles to the equation, it begins to make sense why such a find is considered a treasure.

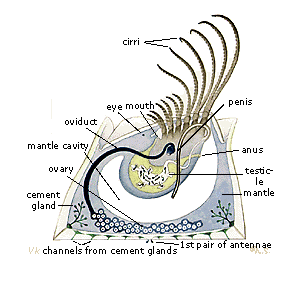

If we do find one, it is always fun to have our divers guess what it is when we get back on the boat and can talk about it. It isn’t often that they guess correctly. They are faced with what looks like a radially symmetrical white shell with a hole in the center. Most people, if they have to guess, think it is a seashell (a mollusk) of some kind. In fact, even scientists thought they were mollusks until 1830. But a barnacle is actually a type of crustacean – a relative of crabs and lobsters. In fact, if you look at the diagram to the left, you can see that the animal looks somewhat shrimp-like.

This confusion is artistically captured in the form of the almost life-sized whale statue in Kalama Park in Kihei.

If you look closely at the belly of the whale in the photo to the right, the artist has sculpted not barnacles, but opihi (limpets) attached to the whale! My mind had to do a little flip-flop the first time I saw this. But it’s understandable. Whale barnacles are a strange life form – and few people will ever have the opportunity to find one on the bottom of the ocean, much less see one attached to a humpback whale in the sea.

Whale barnacles as viewed from above. Broken barnacle on left was found soon after falling off of whale and still has some animal tissue (opercular membrane) visible in the center. Barnacle on the right was found long after falling off of whale. Photo by P. Fiene.

Finding a whale barnacle is the closest some of us will ever come to “touching” a whale. We can’t help but view such a find as good luck. Knowing that this barnacle has traveled thousands of miles on a humpback whale and has fallen off in the exact spot where we are crossing its path is nothing short of spine-tingling.

Written by Pauline Fiene. Photos as credited. Mahalo to Mark Ferrari and Debbie Glockner-Ferrari for sharing their first-hand accounts and documented sightings, as well as wonderfully illustrative photos. Thanks also to Andy Schwanke for use of his whale tail photo and to Cory Pittman for his helpful comments.

*****************

Comments 6

Amazing!! Thank you so much for sharing this with me! I am one of the lucky few that had the opportunity to see it and touch it!!

I learned something today, but I always learn something new when I spend time with you!! Thanks!!

We educate each other 🙂

Aloha and mahalo for the informative article. I just found one at Papa Bay near Miloli’i here on the Big Island at 55′. I posted pics at my Facebook page, and I’ll post the link to your article too.

How lucky and exciting! Congratulations 🙂

Thanks for posting this. I am the author of the 1986 study you cite, and I find your post accurate, very well described and very helpful. It the best documented review of the one-year lifecycle of these barnacles I have come across.

My belief is that the primary cause of barnacles disattaching from the humpbacks has something to do with the warmer waters on the wintering grounds. I don’t know whether that is temperature or lack of food or some other reason. I believe that while some barnacles may be dislodged in intra-specific fights, by predators, or in the course of breaching, those may just be the proximate cause of barnacles that were in the process of falling off anyway.

Thank you, Jim! Thank you for writing the paper and for your thoughts on the reason for the annual loss of a whale’s barnacles.