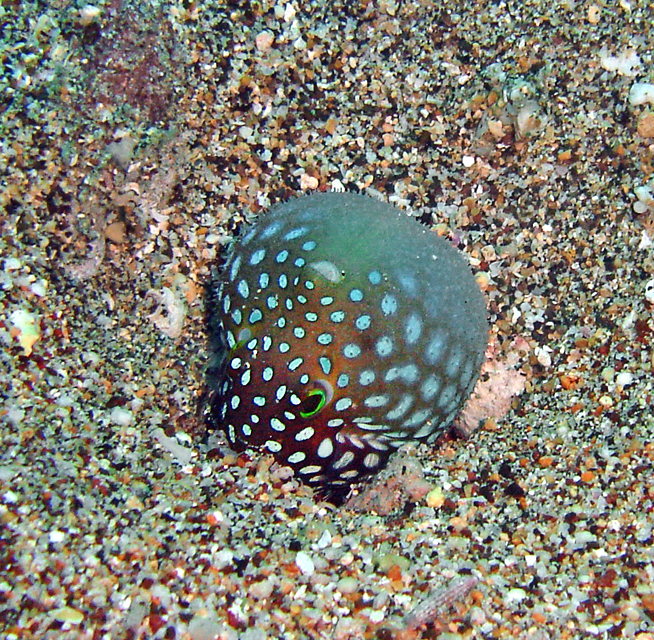

Hawaiian Whitespotted Toby – about 2 inches long. Photo by P. Fiene.

One of the cutest and most talked about fish that divers see in Hawaii is a little pufferfish called the Whitespotted Toby. As adults they are about the size and shape of a partially deflated ping pong ball. They have beautiful green eyes, look a little clumsy moving through the water, and often travel in pairs. Our divers ask about them almost every day because they are just that cute!

A Whitespotted Toby being held in the hole of mystery predator. Photo by P. Fiene.

The Situation

So, when we came upon one in distress, there was no question what we would do. The little pufferfish appeared to be at maximum defensive puffing size. He was being held tightly to the sand with his face up and his tail in a hole. If not for his ability to pump up with water, he would have been dragged into the hole by whatever had a grip on him now.

I had come upon this same scenario years ago, and had been able to free that little pufferfish. As I had done so, I had seen octopus tentacles withdraw into the hole. Naturally, I thought that an octopus might have this one as well.

I put my fingers around the pufferfish’s little body hoping to pull him out of the predator’s grasp. I was surprised at just how firm he was – the hydraulic pressure was much greater than I would have guessed! Another surprise was his skin, which I expected to be silky smooth like an eel, but was instead like soft, nubbly Velcro (visible in the photo above if you look closely).

The Rescue

Whatever had him, though, was not letting go, and I was worried that whatever was in that hole might lash out at (or bite!) my fingers too! So I let go and instead slid my knife into the hole below him. Fellow rescuer and one of our long-time divers, Amy Cole, videoed the deliverance:

Lifting the pufferfish to the side I could look into the hole but saw nothing. And whatever had him would still not let go. So I tried again to free him with my fingers. In a micro-second the predator released the pufferfish which bolted from the hole and deflated – all simultaneously.

After the Whitespotted Toby escaped, a hole similar to this one remained. Photo by P. Fiene.

An open circular hole (similar to the one on the right) remained where the pufferfish had been held to the bottom. It reminded me of the size and type of hole a mantis shrimp would occupy. However, whatever was in there had retreated too far within to see.

In seeming shock, the pufferfish went over to Amy’s husband, Doug, and took shelter by hovering two inches from his tank and BC. This went on for a couple minutes – not normal everyday behavior for a Whitespotted Toby. It was clear to us that he was using the cover that the diver provided in order to calm down and re-orient.

Just before we left the scene the pufferfish, still behaving as if stressed, came over to Amy’s camera and swam back and forth inches from the lens, again seemingly in shock, and using the camera as cover. After about 5 minutes he finally seemed to calm down and swam back down to the sand and rubble bottom.

We continued on the dive and after about 30 minutes returned to the scene. I was anxious to relocate the hole and see if indeed a mantis shrimp were at the entrance to the hole stalking more prey.

The Predator Revealed

But as I approached the location, I saw no hole. I looked more closely and still nothing stood out. Then really really, closely, and THERE HE WAS.

A Giant Mantis Shrimp (aloalo or Lysiosquillina maculata) sits camouflaged under a layer of sand and mucus at the entrance to his hole while waiting to ambush prey. Photo by P. Fiene.

He wasn’t sitting in a nice neat circular hole as I had seen mantis shrimps do previously. Instead he was in the hole and covered with sand except for his incredibly well-camouflaged eyes. I had never seen a mantis shrimp do this!

A Giant Mantis Shrimp (aloalo or Lysiosquillina maculata) exposed at the entrance to his hole. This is how we normally see them. Photo by P. Fiene.

Normally we see mantis shrimp sitting like the one in the photo to the left – exposed at the entrance to their perfectly circular hole. I asked some other long-time Hawaii divers and they had never seen one covered with sand before either. Perhaps it is a common technique, but such effective camouflage that we don’t even notice them.

And apparently our little pufferfish hadn’t noticed him either. Fortunately, he was able to gulp enough water quickly enough to avoid being dragged into the mantis shrimp’s hole. This tried and true defensive maneuver is apparently successful some of the time – but not always. In this suspenseful video from Real Freedom Productions you can see that the mantis shrimp has a difficult time just trying to hang onto the puffed-up pufferfish. What happens in the end could have happened to our little pufferfish. Fortunately, we came by at that critical moment and were able to intervene on behalf of the would-be victim, allowing this little Whitespotted Toby to live another day on the reef.

Written by Pauline Fiene. Photos as credited. Thanks to Amy Cole for video-ing the rescue, and as always to the crew of Mike Severns Diving.

Comments 5

Thanks Pauline, that was really an interesting and fun story.

It’s no wonder you guys have the best dive operation on Maui. You and the rest of your crew have always been the most observant, most knowledgeable, and most patient of any team I have had the privilege of diving with anywhere in the world.

I have gone out with you so many times, yet each time I have learned something new.

Fascinating tale, Pauline. I love those little guys. I’ve seen some with pretty fat bellies and looked it up on the Internet (so it’s true!!!) I read that those are infested with nematodes. Interestingly, it didn’t seem to harm them. Have you heard of that?

Author

Yes, only because I read that in Hoover’s Fish book. Strange. Why aren’t all fish infested with nematodes then?

That’s a good question! I don’t know. But, check out this abstract below on the Toby and nematodes. I guess while they don’t kill them, they do retard their development. The most interesting thing is that infested Tobys eat about twice what a regular one does. Gotta feed those worms!

This study observed differences in behavior associated with parasites in the fish Canthigaster jactator. These fish were observed both within Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaii, and just outside the bay. Normal (unparasitized) fish behaved similarly to their congeners. Behavior varied by size class and presumed sex. Larger fish (males) patrolled territories and courted medium-sized fish (females), which freely crossed male territories. Smaller fish appeared to be immature and remained in limited home ranges on the edge of male territories. All fish parasitized with a philometrid nematode acted most like immature ”normal” fish, with limited home ranges and few social interactions. However, parasitized fish ate at twice the rate of unparasitized fish. All fish collected from the bay contained some parasites, and none were sexually mature, whereas no parasites were found in fish from outside the bay. These data suggest that parasites affect the behavior of C. jactator. Moreover, parasites may limit the sexual maturation of their hosts.

Excellent! It just goes to show you can dive the same place 1000 times (or in your case 6000?) and still find something new! Thanks for keeping the sense of wonder & discovery alive.