What it teaches us for Ukumehame and Olowalu

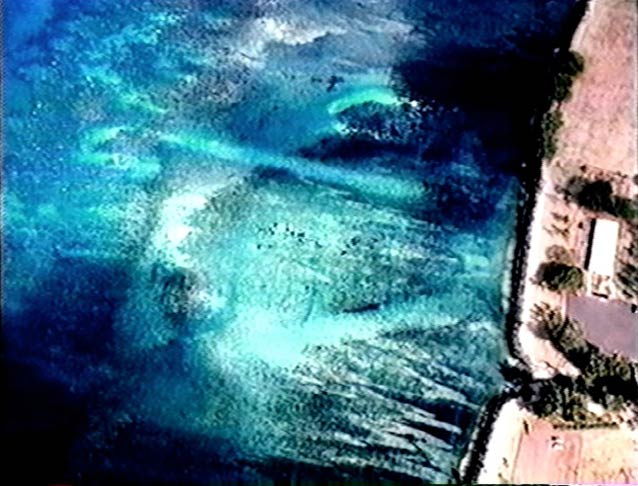

A demolition charge blasting the coral reef in front of Kalama Park to make a better swimming beach.

Photo taken around Sept. 14, 1945 by a member of Navy underwater demolition team 14

Forty years ago a fanciful little piece titled “Our Living Reefs” filled some space in a corner of a page in the The Maui News. It contained flowery words such as “rainbow profusion” and “underwater fairyland.” But it also contained eight surprisingly wise words that we’ve seemingly forgotten today. The eight words were “Not all Maui’s shoreline is protected by reef…”

It is common for Maui’s reefs to be appreciated for their beauty, for providing food, and for attracting visitors, but it is far less common for us to recognize the reef’s ability to protect the coastline. This protective ability of a reef was brought to light in Kihei beginning in the 1940s. A fascinating series of events at Kalama Park began a chain reaction along the coastline to the north and taught a lesson that we should consider in our actions at Ukumehame and Olowalu today.

Prior to WWII Kalama Park was a popular weekend destination for residents who came to enjoy its beautiful beach and shallow water. It was even touted in one newspaper caption as “Maui’s Waikiki Beach!” Can you imagine? It’s hard to believe today because no beach even exists at Kalama Park except for a small damp sliver of sand at low tide. But back then a luxurious wide beach extended from Kalama Park to the north for miles.

During WWII Kalama Park was taken and used as a staging area by the US Army for amphibious assault training. In order to get military craft ashore, the Navy blasted channels in the coral reef offshore. After the war ended, Maui County requested that the Navy blast the rest of the reef in order to make the beach a better “swimming beach” for beachgoers. The Navy complied and in 1945 a section of reef totaling 270,000 square feet or 4-and-a-half football fields was blasted toward the sky.

Kalama Park seawall at low tide – summer 2012

With the reef gone, it did not take long for nature to begin rearranging the sand according to her laws. Because many people felt that the beach was disappearing at Kalama Park, a fortification was proposed, and in 1970-71 a revetment (sloping seawall) was constructed. At that time beaches to the north along Halama St. were still broad and healthy. Halama Street resident Dave Sharp remembers his family riding their horses on the beach, and resident Micky Palmer recalls 70 feet of state land extending seaward from the edge of her family’s property. But the seawall at Kalama Park further upset nature, and the altered ocean flow began removing sand from Halama St. yards as well, forcing residents to shore up their land with seawalls too.

As I type this, coastal hardening with a concrete barrier (seawall) and boulders is occurring at Ukumehame. I have heard the Ukumehame hardening referred to as a band-aid solution. But a band-aid promotes healing. A seawall does nothing to promote healing; in fact, it does damage to adjacent areas.

Shoreline hardening at Ukumehame Aug. 26, 2012

This hardening is bound to have an effect on natural water circulation, as seawalls are known to reflect wave energy, disturbing adjacent areas. In addition, the work itself has disturbed the bottom and is visible as a huge plume of turbid water. This silt-filled water blocks sunlight that corals need to grow. If the reef in this area is killed, we lose the critical protection it provides just as it did at Kalama Park, exacerbating coastal erosion.

Kalama Park is a case study in what happens when we alter a reef and coastline. Have we forgotten that? Or do we just pretend that we don’t remember? It is amazing to me when we have perfect examples of previous human actions – and results – and we ignore them. We have seen what shoreline hardening did at Kalama Park and Halama St. and we need to learn from that.

In the years to come we are going to experience coastal retreat. Sea level has been rising for about 18,000 years and is predicted to continue. Because the island of Maui is subsiding at the same time, sea level rise has been almost 1 vertical inch every ten years, which translates to many inches of horizontal loss.

Let’s honor the knowledge gained by those who have gone before us. The healthiest response to coastal retreat is to not fight nature. Anticipate shoreline loss, don’t build close to shore, and in the case of the pali roadway, move the road inland. If we work with what nature is going to do anyway – with or without our consent – we will move inland and at least preserve the one viable coastal protection that we actually do have – our living reef.

Channels blasted in reef by the US Navy at Kalama Park, Kihei during WWII

****** For a wonderfully informative piece on the chain reaction of events after the reef blasting at Kalama Park, see this 1999 Coastal Erosion in Kihei video put together by the former Halama Street Homeowners’ Association.

Comments 3

How sad that history only teaches those that want to be taught. Olowalu and Ukumehame area, probably the largest and healthiest reef area on the island, is the latest morsel of those that are devouring our ‘aina.

Thank you for this poignant piece! It is amazing to think how short-sighted we can be sometimes. We really need help getting our politicians and decision makers to understand the consequences of losing our reefs – that the tourism economy we have here depends on them in so many more ways than just for snorkel sites.

I enjoyed the posting. Great photo. It really shows you how clueless we were back then. We all know how the highway runs in this area and WHY they are building this structure. So what is the solution? Move the road? Has anyone modeled the new flow this structure will create? It sounds like Kalama Park was a great beach before. Why do they not regrow coral like I see in other countries like Indonesia? Maybe replant the reef? The only modern reef project I know if was when the DLNR dumped the concrete slabs on the living reef. Any positive examples of re-growing coral?

Sean