Divers have so many questions about the other-worldly things we see underwater, but “How long can a Triton’s trumpet live without eating?” was a question that I had never asked myself. A few days ago, however, we were given an “at least this long” answer without even asking.

The Triton’s trumpet (Charonia tritonis) is one of the largest sea snails in the world. We have seen and measured individuals while diving here on Maui with shells that were 17 inches long (they are reported to reach 20 inches). It likely takes years (maybe 10?) to reach this size. And then it probably lives and reproduces for many years after that. So, 20 years or more does not seem unreasonable to me, but I can find no maximum age given in the literature.

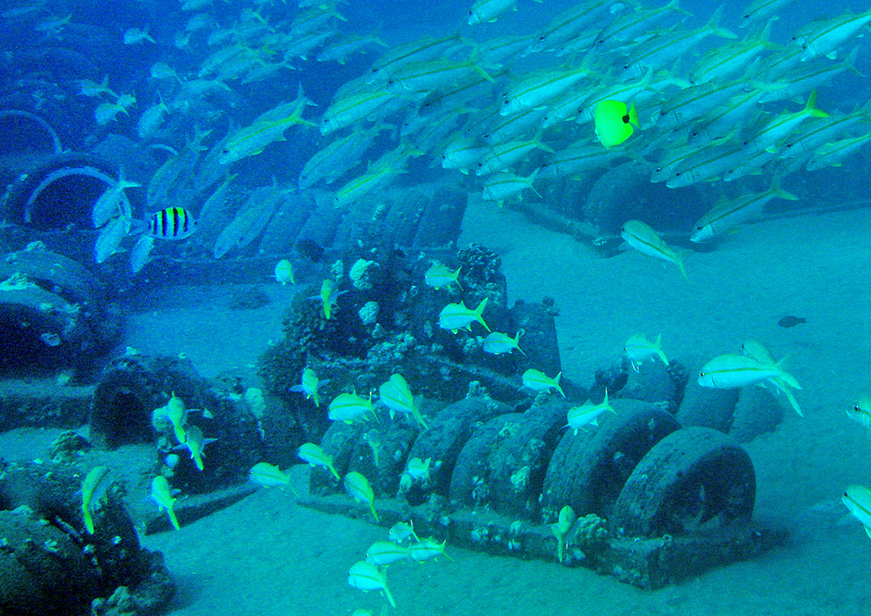

Triton’s trumpets are considered rare across their geographic range and Hawai‘i is no exception. So, when we see one while diving it is kind of a big deal. In the fall of 2020 we were diving on an artificial reef off the coast of South Maui. At that site is a 65-foot fishing boat called the St. Anthony. There are also hundreds of concrete tire modules scattered across the area, some in piles.

This day we spotted part of a Triton’s trumpet in one of the tire modules. Most of the shell was hidden inside a tire module, but its aperture was exposed and facing up toward the sky. I’ve seen numerous Triton’s trumpets mating, laying or tending eggs, or adding to their shell size, but based on this one’s position none of these things was happening. Its position suggested to me that something was not quite right.

I tried to move the shell a little with my hands but it didn’t budge. Still, I thought to myself, “she knows how to be a Triton’s trumpet, surely she knows what she’s doing and doesn’t need any interference from me.” We weren’t operating dive charters then because Hawai‘i was still shut down due to Covid-19, so I didn’t have occasion to think about her again.

Two months later when we were operating again we dived there, but I didn’t happen to swim over that particular set of tires. Fast forward to January 3 when we dived there AND I happened to swim over that set of tires – and there she still was. I couldn’t believe my eyes. I then remembered seeing her months before. She was in the same aperture-up position which made me think that she must have been there that whole time.

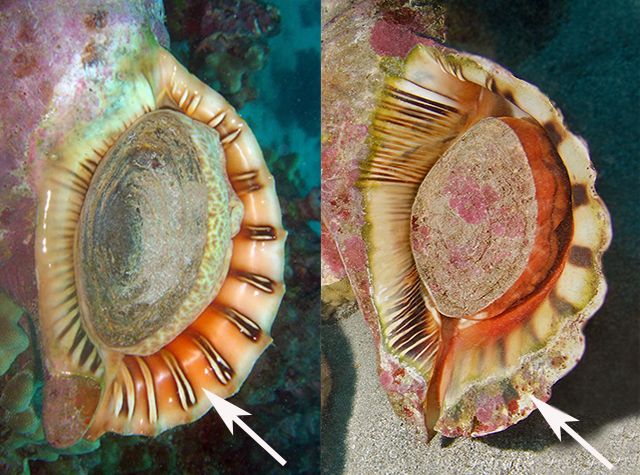

What really convinced me was that the lip of her shell was now colonized by algae and coralline algae, something that would never be the case in a normally functioning individual. She reacted when touched so we knew she was still alive. One of my divers, Keil, tried with great effort to free her, but her shell was solidly wedged. When we surfaced from the dive we already knew that tomorrow we’d be back with a plan to free her.

Right: Lip of stuck Triton’s trumpet colonized by algae and coralline algae. Photo: Susan O’Shaughnessy.

That evening ideas flew around as to how to get her out. The preferred plan ended up being to try and cut the tire with a hacksaw. We had no idea how long this would take and if we would be able to cut enough in the limited amount of dive time our dive computers would give us. Then Andy came up with a better idea which was to shift the concrete tire module which was blocking her in. Warren went down and tied a line around one of the tires and Andy backed the boat up pulling the concrete tire module away just enough to create a space for her to be removed from her prison. The amount of time that had passed since we first saw her in that tire – FOUR months!

After Warren freed her he left her aperture-up on the sand next to the tires. When we went down 20 minutes later she had turned herself over. We took this as a good sign that she had had the energy and strength to do that.

We placed her in a tire module facing out so that she could crawl out when she was ready. Oh, how wonderful it would have been if we could have stayed there to see her extend her foot from her shell and emerge from that tire. Would she feel a snail’s sense of “freedom”? Relief? Joy? Or just HUNGER?

Triton’s trumpets feed on a variety of echinoderms. We have seen them eating sea cucumbers and sea urchins on occasion, but their primary prey is a variety of sea stars. Their preferred sea star is the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci in Hawai‘i), a voracious coral-eater that has occasionally experienced population outbreaks on reefs around the world. These outbreaks most likely occur as a result of larval or recruitment success, but having Triton’s trumpets around to eat adult crown-of-thorns might also play a role in keeping their numbers under control. Recent research indicates that the mere presence of Triton’s trumpets may act as a biological control by keeping crown-of-thorns away due to chemical signals emitted by the tritons.

Given the potential positive impact that Triton’s trumpets have on reef health, and given their low numbers, saving just one large female of reproductive age like this one could have had a tiny impact on our local marine environment.

One reason for their low numbers may be that they have been victim worldwide to collecting and to the shell trade. As a result Australia, India, Indonesia, Philippines, Guam and many other countries have banned their collection or exportation, but Hawai‘i has not. Efforts are underway right now to change that.

As a side note, a different Triton’s trumpet had been hanging around within about 10-20 feet of her since at least November right up until now (January). We’ve recorded mating October through December, and egg-laying and development from December through April. My theory is that this second triton is a male and he has been picking up her chemical scent this whole time, but has not been able to get to her. A patient snail indeed. Hard to imagine that she would have anything on her mind except eating, however, after her four-month fast.

by Pauline Fiene. Photos as credited.

********************

M.R. Hall, C.A. Motti and F. Kroon (2017) The potential role of the giant triton snail, Charonia tritonis (Gastropoda: Ranellidae) in mitigating population outbreaks of the crown-of-thorns starfish. Integrated Pest Management of Crown-of-Thorns Starfish. Report to the National Environmental Science Programme. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (58pp.).

Comments 10

Perhaps the other triton was delivering food to her all the time?

You’re such a romantic, Tommy!

You’re Amazing!!!! Mahalo for all you do!!!

Love your rescue story!!! I recall one special dive watching a Triton chase a Crown of Thorns…a slow motion race to be sure. By the time our tanks were exhausted the Triton had won and was beginning what looked to be a very long feast!

From a northern Wisconsinite. This was wonderful as I watch my lake’s ice cover slowly melting! Thank you. I have niece living on Maui who sent it to me. carol alcoe@ gmail .com

Mahalo for the rescue and the story! Any idea how the initial wedging occurred? She … tripped? Reached for prey and fell over the edge? Was discovered by a diver, then carelessly (or cruelly) repositioned so? Inquisitive dolphins jostled her but, thumbless, couldn’t retrieve her? Local quake jostled things just after she’d eaten a huge meal so, though initially barely trapped, she was able to grow a little bit and be more firmly trapped? Regardless, I can’t wait to return and look for her!

Author

All I can think, Charlie, is that these snails did not evolve in an environment of tires and concrete, and as a result of maneuvering in such an unnatural environment, she just plain got stuck.

Please let us know when you see her again! One more question: I have seen them move forward, and even turn (a few degrees). Do they have a reverse gear?

Author

They do not.

Thank you for sharing this story and rescuing such a beautiful and critical animal! I hope there’s another installment to her story in the future.

I’m sorry if this is the wrong place to ask, but I’ve searched the internet for ages and have yet to find a solid answer. How do Tritons grow their gorgeous huge shells?! You alluded to the process in the story. Is their shell somewhat malleable while they are alive? I’ve read that new shell material is added at the varices stationed along the spire, keeping them evenly spaced with the aperture, but don’t understand how the hard shell makes room. Specimens I’ve scrutinized look like each new whorl grew over the previous one, the older lips and canal still visible. But that seems like an incredible amount of growth all at once. Was each “old” varix at one time the shell’s aperture? A 20-year time lapse video would be SO helpful 🙂

Any insight (or link/book redirect) would be greatly appreciated.

Happy holidays & new year!

Jonathan