This summer’s and fall’s high ocean temperatures and sunlight intensity have taken the lives of thousands of coral colonies in Hawaii. Some places have lost large amounts of colorful, vibrant coral reefs and in their place is a covering of dark brown algal turf. It has brought some people to tears.

Last Saturday morning DLNR held an event called Bleachapalooza which encouraged snorkelers and divers to go out and report on the status of their favorite reef; to take notice of the reef composition, percentage of bleached coral, which species were bleached, etc. Then they were asked to fill out a form on the Eyes of the Reef website to add to what is known about the extent of bleaching at this point in time – a sort of “State of the Bleach.”

So, to participate, I headed over to Maui’s cherished reef at Olowalu. I had been there the week before in a very shallow part of the reef and had come out of the water in tears. Although this had all been predicted, I had not been able to envision what it would look like if large areas of coral subsequently died after bleaching. I did not want to go back – at least not until months had passed and some recovery could be seen.

Lobe coral colony (Porites lobata) at Olowalu estimated to be about 500 years old. As seen on Google Earth.

But in honor of the event I did go back for a very specific reason. I went to visit a particular coral colony that has special meaning to me. It is one of the oldest circular coral colonies at Olowalu. Measuring at about 25 feet in diameter, it has been estimated to be about 500 years old*, and is so large that it can be easily seen on Google Earth.

Hovering in the water in the presence of this coral elder is like visiting a museum and beholding an incredible sculpture from another age. This colony, and others in its age class, precedes Western contact! Just imagine everything that has taken place on land during this time, while this one particular colony quietly grew, partly died back during unfavorable conditions, then grew some more…

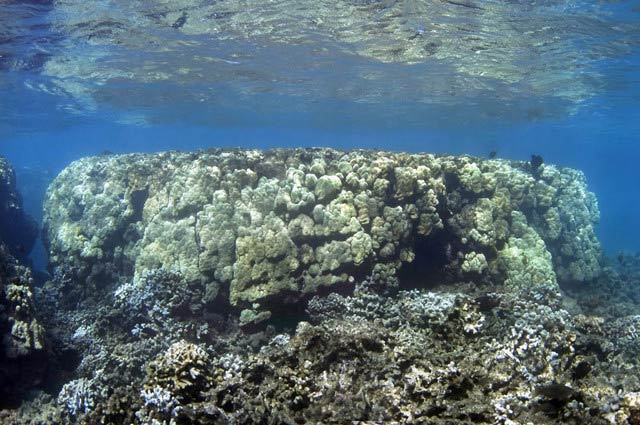

This is what it looked like from underwater in August of 2013. Even then there were areas of die-back among the living parts, but most of it was alive. It was an impressive sight.

Estimated 500-year-old lobe coral colony (Porites lobata) at Olowalu photographed on Aug. 24, 2013. Photo by P. Fiene

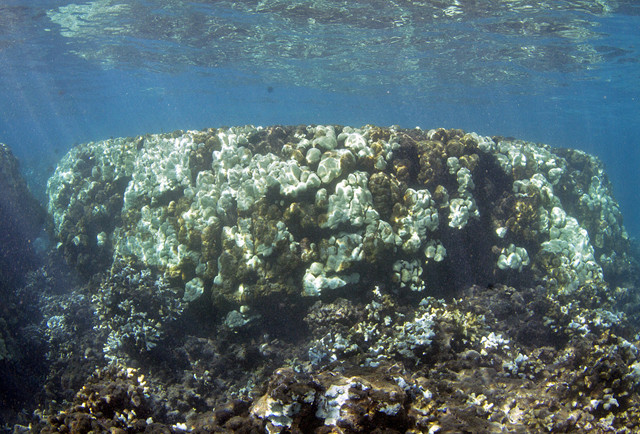

From what I had seen the week before, I had very little hope for what I would find. The water was not the clearest and as I approached the dark silhouette in the distance I was expecting another wrenching sight. BUT – most of it is surviving! Yes, there are patches that have recently died and are covered by algal turf, and yes there are still several weeks ahead of higher than desirable water temperatures, but at this time it has not died as so many thousands of coral colonies here in Hawaii already have.

Estimated 500-year-old lobe coral colony (Porites lobata) at Olowalu photographed on Oct. 3, 2015. Photo by P. Fiene

Should we be surprised? The saying that “old age isn’t for sissies” may hold true for corals too. For this colony to have survived hundreds of years it must have adapted to many different environmental conditions along the way, some of them unfavorable and challenging. It is suffering again now, to be sure, but as of Oct. 3 it is still alive!

We will keep you posted about this very special coral colony in the months ahead.

by Pauline Fiene. Photos as credited.

**********************

*Rough age calculated by dividing the 25 foot diameter in half = 12.5 feet. Converting to centimeters = 381 cm. Then dividing 381 cm by .71 cm (Edmondson’s mean linear growth rate per year for 10 Porites lobata colonies) = 537 years.

Edmonson, C.H. 1929. Growth of Hawaiian Corals. Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Bulletin 58, Honolulu, Hawaii.